Testing Ideas for Corporate Innovation: Slow, Steady, and Disruptive

Corporate innovation often presents unique challenges, demanding a careful balance between creativity and actionable results. In an episode of the Around the Product Development webinar, we had the opportunity to talk with Ignacy Studziński, Venture Architect at The Heart. Ignacy shared his expertise on testing ideas within corporate environments, drawing from his extensive experience with startups and established organizations. Curious to learn how ideas are born, validated, and scaled in the corporate world? Read on or watch the full conversation.

Table of contents

Matt (Host): Welcome to Around the Product Development, our weekly show where we, in 25 minutes, feature lively discussions on hot topics all about digital product creation. We talk about topics from monetization to innovation, and we cover all of that in just 25 minutes.

This week, we have a very interesting topic. We will talk about testing ideas for corporate innovation under the title Slow, Steady, Disruptive. Generating ideas in corporations is difficult and has many hurdles – bureaucracy, slow decision-making, and risk aversion in the culture that may deter innovative thinking.

Today, we’re going to talk about all of that with our guest. His name is Ignacy Studziński – I hope I said that correctly – who is a Venture Architect at The Heart. Ignacy is based in Warsaw, Poland. He has also worked as a consultant at Ernst & Young in the past, which is interesting as well. Ignacy, maybe you can introduce yourself a little.

Role of a Venture Architect and the Startup Studio Model

Ignacy (Guest): So maybe I’ll start straight from my venture building experience, as this is one of the most relevant aspects for today’s topic.

I’m a Venture Architect, as you said. What we, as Venture Architects, do is shape and test business ideas. Yes, I work in a startup studio called The Heart. Let me explain what a startup studio is. It’s a relatively new model in Poland and, more broadly, a new model that is expanding very quickly, though it still requires some explanation.

The startup studio focuses, as the name suggests, on building a portfolio of startups from scratch. Different startup studios have different areas of focus.

Our focus is on building corporate-backed startups. I have experience working with innovation and product teams from various institutions, such as banks, financial institutions, retail, the real estate industry, the energy sector, and also with individual founders.

Defining Corporate Innovation and Its Challenges

Matt: We talked today about testing ideas for corporate innovation, which can be challenging for corporations. What does corporate innovation actually look like, and what do we mean by it?

Ignacy: Okay, so when I think about corporate innovation, it’s the new ideas that come out of well-established organizations. Not from founders working on something in their basement, but rather ideas that emerge from corporations. As you mentioned, it has its challenges. Let me name a few, starting with one that might not be so obvious.

Not all companies actually need new ideas at a given moment because they’re doing really well. They’re focused on exploiting already successful businesses rather than looking for something new. I think that’s one drawback and a real challenge when working on new ideas in a corporate environment.

Another challenge is that, from my perspective, innovation is a relatively new topic, so not every organization has a well-structured approach to it. There’s no standard for generating ideas. I think Google has what we might call the “gold standard.” They allow employees to spend 20% of their time working on their own ideas, iterating on concepts, and building them. This is a great approach, but it’s not the same in every organization.

Innovation, in general, is difficult. It’s not easy to come up with new ideas, and as you mentioned, it’s even harder in a corporate environment.

There, you have your reputation, your brand, and you’re known for something specific. No one wants to be seen as the person with bad ideas, right? I think a mindset shift is necessary to allow ourselves to come up with ideas and let them leave the boardroom to eventually reach real customers.

Five Sources of Ideas in Corporate Innovation

Matt: Some companies may not need innovation if things are going well. Others, however, recognize its necessity due to market changes, emerging trends, or developments like AI, fearing their position could weaken. What challenges do they face, and where do their ideas for innovation come from?

Ignacy: You already mentioned some sources, so let me break them down into five key ones.

The first, and most important, is identifying problems. These could be customer problems, identified by teams like customer success or support, or internal issues within the company. Innovating based on internal problems can lead to scalable solutions. For example, Atlassian created Jira and Confluence by solving their own internal challenges while working with customers.

The second source is inspiration, often driven by competition or observing what startups in the field are doing. Decision-makers, such as CEOs, might experience FOMO and want to replicate or adapt successful ideas.

The third is leveraging distribution channels. Microsoft is a great example – their products are already widely used, so introducing new ones is easier. When they launched Microsoft Teams, they could rely on their existing user base, unlike Slack, which had to build its market presence from scratch.

The fourth source is monetizing unique resources or competencies. Amazon, originally a bookstore, leveraged its infrastructure to create AWS, which now generates a significant portion of its revenue. This demonstrates how unique internal capabilities can lead to entirely new business models.

Finally, trends and external factors, such as AI, also play a role. For instance, two years ago, PKO Bank became the first Polish bank to open a branch in the metaverse, aligning with a growing trend.

These five sources – identifying problems, inspiration, distribution channels, monetizing resources, and trends – are the most common ways ideas are born in corporate environments.

The Role of Organizational Structure in Innovation

Matt: Do you feel that some of these sources are more common than others, or is there no clear trend? Do ideas come equally from all these sources? In your daily work, do you see that most ideas come from a specific trend or hype, for example?

Ignacy: It’s difficult to say because it really depends on how the organizations are structured. If they have access to top talent in software development, they’re more likely to build something quickly. Ideally, if they have strong research teams, they focus on foresight – thinking ahead to identify the next big global problems. When it comes to identifying problems, it’s not just about the industry, but also about the organization’s mindset, talent, and internal resources that enable ideas to emerge.

Matt: Once ideas emerge, how do you validate them? Whether they come from employees, trends, or even a CEO inspired by an AI article, what’s the next step?

Ignacy: Validation is a process, and it ties closely to the issue of failure. Large organizations are often uncomfortable with failure because they have so much at stake. They risk far more than a startup that no one has heard of yet.

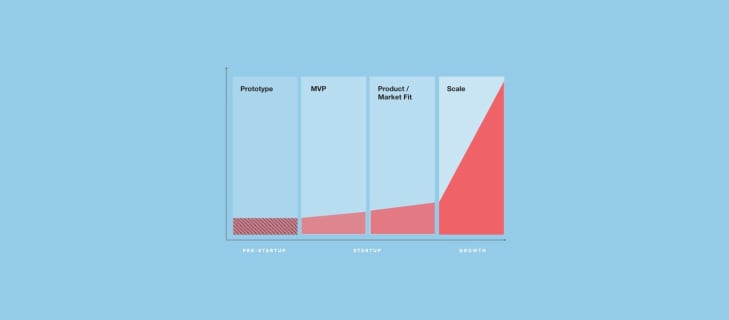

To navigate this, we often use frameworks like those taught in the Lean Startup methodology: build, test, and learn. However, applying this in a corporate environment is not easy.

Organizations tend to do better when they focus on ideas in areas they’re already familiar with or when they leverage their internal resources, such as IT talent. This avoids the need to hire an external software house, which is costly and risky if the company is still unsure whether they want to pursue the idea.

Practical Tips for Innovators and Decision-Makers

Matt: We’ve focused on corporations, but these insights can also help non-technical people, like those with a startup idea. What tips do you have for turning ideas into reality or testing them?

Ignacy: Yeah, I prepared something—I have it on a post-it note. Interestingly, the post-it note itself is an example of corporate innovation, created by accident. You can look into that later.

I have two tips for innovators inside companies and one for decision-makers. If you’re an innovator within an organization, you need to convince decision-makers to move forward with your idea. Two things you can do are, first, gather insights—about almost everything, but most importantly about customer problems. Speak from the perspective of what you know about these problems and how your solution addresses them.

Rather than just showcasing something you’ve built (even if you’re a technical person), focus on clearly showing the specific problem your solution solves. Second, visualize what you’re working on. Find benchmarks or examples from other companies or markets. This helps decision-makers visualize your idea and see its potential.

For decision-makers, it’s essential to align KPIs. People are typically rewarded for doing their daily work well, but they are rarely rewarded for coming up with ideas. Figure out how to align KPIs in a way that fosters a culture of innovation in your organization. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but aligning incentives can make a big difference.

Matt: I’m curious—if someone has a great idea, what’s the first step? Can they contact you? How does it work for a venture-building company or corporations looking for ideas? Does it always work this way, or can it go the other way around?

Ignacy: It works both ways. Actually, we’ve done a lot of projects for companies that wanted to get inspired. For example, they might ask us to showcase startups in a specific category. Regarding your question, my team and I really enjoy hearing about two things: challenges and ideas from corporations. Maybe challenges even more than ideas, but both are valuable.

Every venture-building project starts the same way. It could begin with just a one-sentence description, and we work from there.

If you have an insight that something might be valuable for a particular group of people, bring it up. That’s all we need to get started.

Matt: And that brings us to the end of our webinar. I think we covered everything, and it was quite extensive. For me, it was incredibly interesting to learn how venture-building works and what you’ve accomplished. I’m sure many people out there have ideas they’re carrying around, or they work at companies but aren’t sure what to do with them.

I think we’ve provided valuable insights for both groups. Thank you again for your time. And to our audience, thank you for joining us—see you next time. Bye-bye!

Share this article: